Archives

Foodservice Packaging and… Landfills / Municipal Solid Waste

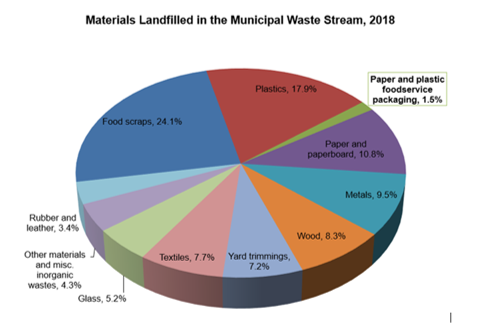

/in Stewardship ResourcesThe most persistent environmental myth about foodservice packaging concerns its role in the solid waste stream, and particularly that which ends up in landfills. Year after year, data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency shows that paper and plastic foodservice packaging products make up a tiny portion – under two percent by weight! – of the municipal solid waste sent to landfills in the United States. Compare that to other items that end up in landfills:

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (November 2020) Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: 2018 Tables and Figures.

Updated March 2021

Foodservice Packaging and… Fluorochemicals

/in Stewardship ResourcesFoodservice packaging is made from a wide variety of materials. These products go through rigorous testing to ensure that they meet stringent regulations, ensuring the safe delivery of foodservice items to consumers.

However, there has been some confusion over the safety of some chemicals used in the manufacture of paper foodservice packaging, particularly claims that certain coatings are “toxic” and dangerous to human health and the environment. All Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) chemicals are not the same and should not be treated the same. The truth is…

-

- Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of over 3,000 synthetic, man-made chemicals. They are also referred to as “polyfluorinated chemicals” (PFCs). There are variations within this large class of chemicals, including their properties, toxicity and intended use.

- Certain PFAS may safely be used in some paper foodservice packaging items likes wraps, food containers and plates to prevent oil, grease and water from leaking through the package onto skin, clothing, furniture, etc.

- Two common sub-categories of PFAS include:

-

- “Long chain” or “C8” chemicals, since they have 8 or more carbons in their structure. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) are two examples. It should be noted that PFOA and PFOS — the subject of much attention these days by regulators, the media and environmental groups — were not used in food packaging applications. In addition, long chain PFAS chemistries were voluntarily phased out and are no longer allowed in the U.S., Canada and other parts of the world.

- “Short chain” or “C6” chemicals, since they have 6 or less carbons in their structure. Manufacturers of these newer chemicals — like all chemicals that may come in contact with food — submit their specific formulations to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, Health Canada and other appropriate regulatory agencies for rigorous review.

-

-

- In August 2020, the U.S. FDA announced a voluntary phase-out plan for a certain type of short-chain per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), that contain 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (6:2 FTOH), which may be found in certain food contact substances used as grease-proofing agents on paper and paperboard food packaging.

-

- Other PFAS chemicals, with proper FDA Food Contact Notifications (FCNs), may continue to be used.

- While some paper foodservice packaging may continue to use approved PFAS chemicals, other packaging items may be manufactured without the use of them. As non-PFAS alternatives are introduced, performance, price and market availability are all factors that will impact their broader use and acceptance

- Unfortunately, testing for PFAS chemicals remains inconsistent. Recent studies tested for the presence of fluorine to determine whether PFAS was used in food packaging. While the test may be an indicator of the use of PFAS, it does not differentiate between “long chain” or “short chain” PFAS, and it may not provide accurate results. The presence of fluorine does not mean the presence of PFAS.

Foodservice Packaging and… Black Plastics

/in TechnicalFoodservice packaging is made from a wide variety of materials. These products go through rigorous testing to ensure that they meet stringent food packaging regulations, ensuring the safe delivery of foodservice items to consumers.

However, the safety of foodservice packaging made from black plastics has been called into question recently, with claims being made that recycled plastic from electronic parts are being added to plastics used to manufacture items like take-out containers and cutlery, leading to the presence of hazardous chemicals.

The truth is…

- The Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada, which regulate materials that come into contact with food in the U.S. and Canada respectively, do not allow non-food-grade plastics, whether from virgin or recycled sources, to be used when manufacturing foodservice packaging.

- While bromine/antimony flame retardants may be used in plastics associated with electronics, they are not used in the resins produced to manufacture foodservice packaging in the U.S. and Canada.

- Additionally, mercury, lead, cadmium and hexavalent chromium (also known as “CONEG 4”) may not be used in foodservice packaging in the U.S. and Canada.

- The mere presence of chemicals deemed hazardous does not mean a true health risk exists. Ambient or unintentional additions of chemicals could possibly occur, but these exist at trace or extremely low levels, far below the rigorous testing standards set out by international regulatory agencies.

- Plastics from electronic waste may be recycled, but these materials are sold to very limited, very specific markets (often outside North America). These markets do not include food-grade plastics.

Consumers can be assured that black plastics used to make foodservice packaging in the U.S. and Canada has been deemed safe for use by the appropriate regulatory agencies… and that means plastics from electronic waste was not used to manufacture it.

For more detailed information on recycling and plastics used in food-contact applications, please check out these resources:

From the U.S. Food and Drug Administration:

- Recycled Plastics in Food Packaging

- Guidance for Industry: Use of Recycled Plastics in Food Packaging (Chemistry Considerations)

From Health Canada:

Published September 2018

Market Research Resources

/in Publications and ReportsOne of the most common questions we receive at the Foodservice Packaging Institute is “Do you have market research data on the foodservice packaging industry?” The answer is yes — but most of it is for FPI members only.

- Beverage Cups

- Cup Sleeves

- Lids and Domes for Beverage Cups

- Straws and Stirrers

- Beverage Carriers

- Portion Cups

- Plates, Platters and Bowls

- Domes for Plates, Platters and Bowls

- Food Containers and Pizza Boxes

- Wraps in Sheets

- Foodservice/Cafeteria Trays

- Single Portion and Carryout Bags

- Cutlery

- Napkins and Placemats/Tray Covers